Is Make America Great Again Fair Use?

D onald Trump has done pretty well for someone ridiculed by well-nigh of the liberal media as an breathless babbler. His candidature speeches were simply "word salad", people chuckled. But the speeches worked. And they did and then considering Trump is a brilliant and careful rhetorician. His can-do slogan of renewed domestic celebrity – "Make America Nifty Again" – won over Hillary Clinton's … well, what was hers, again? Oh, yep, "Stronger Together" – which met exactly the same fate every bit the Remain campaign's insipid "Stronger In".

In the language of political soapbox analysis, greatness and strength are both examples of a frame: a guiding metaphor or image for a political argument. It is hit how frequently Trump deployed the frames of beauty, happiness and optimism: "Y'all're going to exist and so happy; you're going to exist and so proud," he would beam, even equally he curried favour with racists. Frames tin can inspire. But they can likewise deceive.

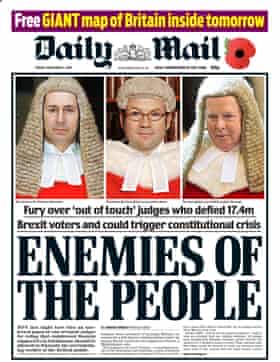

As another case, nosotros hear a lot almost "the British people" these days. The three judges who ruled on the Article fifty challenge were called "enemies of the people" past the Daily Mail, while the Telegraph spoke of "the judges against the British people", even though the decision dedicated British citizens' right to parliamentary representation against the arbitrary do of executive power. This atypical "British people" has come up into peculiar focus since the Brexit vote. As Theresa May said over again this month: "The British people, the majority of the British people, voted to leave the European Marriage." The "people" voted; at present the supposed "will of the people" must be respected. Except they, and it, are purely imaginary.

Photo: Paul Sancya/AP

The Brexit vote was carried by 27% of the population, or 37% of the electorate; slightly fewer voted for Remain; the stance of the balance of us is unknown. Clearly, the picture of a single British "people" with a unified "volition" on this issue is a fiction. (Nor, for the aforementioned reasons, did "the American people" vote just for Donald Trump: more than people voted for Clinton, and about 42% of the electorate didn't bother to vote at all.) "The British people", and so, is just another frame, to eternalize the go out campaign's successful deployment of the frame of taking dorsum control. Now, it appears the state has a choice between a "hard Brexit" or a "soft Brexit": a frame that may seem to favour the pro-EU side if one thinks of difficult and soft landings, or their opponents if i favours tumescent strength.

Frames are often imposed by ways of subtly manipulative linguistic communication – Unspeak, or argumentative soundbites. (The idea that Britain should "take back command of our borders", for example, dishonestly unsaid that we had no control over them beforehand.) But the aforementioned frame can be invoked by many unlike forms of words. Also office of the get out campaign's "control" frame, for example, was the emphasis on making our own laws and reclaiming our sovereignty (something else we already had, as evidenced by the very fact we are able to get out the EU).

Political arguments are ofttimes conducted as a clash of frames. Control or strength? Security or empathy? And successful social and political reforms tin can be accompanied past clever reframings. In the US, "gay marriage" or "same-sex marriage" was redesignated "spousal relationship equality". Now, the frame was not 1 of homosexuality, only one of equality: of simple fairness. And in this way, or then it might appear, prejudice was overcome. On the other hand, the faultline over abortion rights in America is symbolised past the incommensurable frames in which the outcome is couched: one side uses the frame of life ("pro-life"), the other the frame of selection ("pro-choice"), and never the twain shall meet.

Frames are all around usa. They saturate political and social soapbox. Some call back this is only the style mass political communication is bound to work, but others say it doesn't have to. Must we always fight framing with framing, or is information technology time to try something different?

In contempo years, it has get fashionable in political psychology to say that, broadly speaking, liberals and conservatives respond positively to dissimilar sorts of frame. This is one of the ideas promoted by the cognitive linguist George Lakoff, whose pop book on framing, Don't Retrieve of an Elephant!, became a boxing transmission for despondent Democrats later George W Bush's second election victory. In an earlier volume, Moral Politics, Lakoff suggested that a major deviation between conservatives and liberals lies in their mental models of the family unit. Republicans honey a "strict father" frame, while Democrats prefer a "nurturant parent" flick.

In this sense, Lakoff pointed out recently, Trump is not some baroque perversion of Republican party politics; on the reverse, he played the campaign as the ultimate "strict male parent", threatening to ban Muslims and Mexicans from entering the country, and ready to insult anyone who disagreed with him. He, Lakoff argues, "is a businesslike bourgeois, par excellence" – likewise as a main of political framing.

Another model of liberal v bourgeois frames has been adult by the psychologist Jonathan Haidt. His "moral foundations" scheme lists six axes along which people brand political value judgments: intendance/harm, fairness/cheating, freedom/oppression, ingroup loyalty/expose, authorization/subversion and purity/degradation. Research suggests that liberals respond more strongly than other people to arguments within the "care" and "fairness" frames, and less strongly to the others. Conservatives, meanwhile, respond more than or less equally to all six. This is offered every bit one explanation as to why the frames of strength and group loyalty, for case, are traditionally rightwing appeals, while the left invoke empathy and egalitarianism.

Some people suggest, indeed, that this divergence makes a conservative's candidature task fundamentally easier than a liberal'southward, as Aleksandra Cichocka, lecturer in political psychology at the University of Kent, explains. "Research shows that people endorse rightwing ideologies because they offer feelings of security, certainty and power," she says. "It has been argued that correct-wingers hold a sort of psychological advantage, considering they provide simpler and possibly less ambiguous ideas on how society should work. Such ideas would be peculiarly appealing to those who have been feeling powerless or out of command, and the contempo economic crisis or increasing terrorist threats might have made people peculiarly prone to feel this mode."

The Brexit and Trump campaigns did employ what are oftentimes thought of as rightwing frames – but non simply those. Jim A Kuypers, professor of political communication at Virginia Tech and the author of several books on frame analysis, observes that both campaigns employed "a great deal of safety talk", as well as emphasising in-group loyalty – "citizens of the U.k., not the EU; Americans outset; not the world".

Merely Trump too exploited the frames that supposedly entreatment most to liberals. "I think function of Trump'due south entreatment," Kuypers suggests, "is that he is too speaking out using the impairment/care and fairness/cheating categories" – in other words, those theoretically endemic past his opponents. Trump claimed empathy for downtrodden American workers, while the aggressive moniker "Kleptomaniacal Hillary", nevertheless unfair in fact, evidently stuck.

The thought that the right are better at framing than the left has been common since the early 2000s, but in that location are differing ideas about why information technology should be so. Some people recollect rightwing frames are more attractive to many people considering they are elementary and easy to empathise. Some, like Lakoff, think the problem is that Democrats have not taken framing seriously plenty to do it right. Others add that institutions are key. Rupert Read, a philosopher at the University of East Anglia and a Green party activist, runs the Green House thinktank and the "Green Words Workshop", whose aim is to explore means of communicating ecological issues more powerfully to the public. "Far more than resourcing is needed," he says, for the left to match the framing power of its adversaries. "That'southward 1 of the issues; nosotros need the kind of network of thinktanks, foundations etc that the right has. Coin matters!"

And then what is to be done? Read, like many others, thinks those on the left ought to be bolder about "framing for success". "We tend too frequently to act like a bunch of policy wonks, rather than a bunch of people out to win," he says. In his 2022 report, Post-Growth Common Sense, he suggests that the very idea of "the environment" suggests that nature is something outside ourselves, and that "sustainability" implies simply adjusting the current organisation so that information technology can keep going for ever. Instead of "sustainable development", he suggests that Greens should adopt a frame of "environmental citizenship". Opposition to economic growth to its ain sake should exist framed not as "limits to growth" or "degrowth" simply as "one-planet living".

Lakoff, meanwhile, advises Democrats to pivot to the frames of "public" and "freedom". Stop defending "the government", he says, and instead talk near "public resource", "public servants", and and so forth. "And accept back freedom," he advises. "Public resources provide for freedom in private enterprise and individual life." He fifty-fifty suggests that progressives should "give up identity politics. No more than women's issues, black issues, Latino issues. Their issues are all existent, and need public discussion. Just they all fall under freedom issues, human problems."

He sums upward his advice to progressives: "Empathise what you believe. Say what you believe and exist honest. Empathize that other people have a different worldview. Understand that most people are biconceptual" – liberal on some subjects, conservative on others. "Speak to that aspect of the biconceptual encephalon that has empathy," he advises. "Bring the science of heed into public discourse." All that, he adds wryly, is of course "a tall order".

Others, however, are sceptical that some kind of "skilful" framing can defeat the bad. In his recent book Plenty Said, Marker Thompson, the old director-general of the BBC, argues that framing and spin have rendered the political environment toxic. He calls on politicians to prefer, instead, a mode of "critical persuasion", treating the public like adults, and speaking honestly about the difficult tradeoffs involved in any decision. If aggressive framing by the right is somehow misleading and dishonourable, why should it exist acceptable for the left? There is no perfectly neutral language that is completely free of framing, but clashes of highly strong frames can hands just atomic number 82 to entrenched positions in a kind of frozen rhetorical war, as with the pro-life versus pro-selection standoff in the US.

And what if the overarching frame that governs our political disagreements is itself poisonous? Besides much of politics right now, Kuypers says, is conducted within a "tragic frame", in which: "The other person or side is demonised, wrong, evil, needs to be punished. I believe this is an easier behaviour for liberals to engage in given that their moral foundations are so strongly linked with harm/intendance and fairness/reciprocity, although conservatives are non allowed to this past any means. Only how easy is it to demonise someone when you view them as unfair and harmful to the equitable view of humanity to which you subscribe?"

Clearly, this is already happening with Trump and Trump supporters. Things would exist more than civilised, Kuypers suggests, if nosotros switched to a comic frame, which the bourgeois philosopher Edmund Burke defined as one in which people are "necessarily mistaken [and] all people are exposed to situations in which they must act every bit fools".

But there is a deeper problem with liberals' hand-wringing over the notion that the right are then much ameliorate at framing than they are. It is that information technology implies an uncomfortable theory of false consciousness amongst the benighted ordinary folk who vote for rightwing causes and politicians. They must be blinded by the frames; they could not possibly be deciding on the basis of the actual people and policies. Could they?

Well, perchance they are. It could very well exist that the success of the fashion the Brexit and Trump campaigns were framed was just a symptom of something larger, rather than the proximate crusade of victory. "Maybe the appeal of certain frames depends mainly on the real prevailing social conditions at whatever given moment," suggests Deborah Cameron, professor of linguistics at the University of Oxford. "The anti-European union lot have been lament about loss of sovereignty since we joined, but information technology took a prolonged period of deepening inequality and social upheaval to give Brexit traction. Or in other words, maybe information technology's not primarily a question of how things are represented. Trump didn't create his angry white public; they created a space for him to fill."

The documentary film-maker Adam Curtis agrees that the framing is secondary. "I don't call back that the attraction of Trump or Brexit has much to do with the 'stories' they tell," he says. "I'thou not sure people believe those either. What they both do offer people is a giant button with 'Fuck off' written on information technology in giant messages. And faced with a distrust of all the old frames, a lot of people want to printing that button."

Curtis argues that the ability of political framing may be on the wane, considering the rise of individualism, particularly in the atomised world of social media, is an existential challenge to mass commonwealth itself. "To shape the world they style they want, politicians accept to assemble the masses together. That's what gives them ability." (They need to convince us, to render to our earlier instance, that we are "the British people" or "the American people".) "And the manner they do it," Curtis continues, "is by persuading people to give themselves up to a compelling story. In an historic period of super-individualism that's impossible – it becomes like herding piglets, considering everyone wants to define their own story and definitely not give themselves upwardly to the political leader'southward frame."

So where will the next big stories, the frames of the time to come, come from? "In that location is evidently a existent hunger for something that allows you lot to challenge a organisation in which many people feel more than and more helpless," Curtis says. "I don't think Donald Trump or Brexit are that – but they are straws in the air current." He doubts, too, that a simple return to nationalism is the next epochal frame. Perhaps, he suggests, information technology volition come from faith or science. But whatever it is, he points out, it "volition accept to square the circle. It volition make you nevertheless experience that you are an individual in control of your life and feelings. But also make you lot want to give up yourself to some g picture of the futurity. Someone who manages to put those ii together is going to be very powerful."

Many might fear that Trump is already that man. Simply what if he is only a John the Baptist to the real framing messiah to come?

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/13/make-america-great-again-why-are-liberals-losing-the-war-of-soundbites

0 Response to "Is Make America Great Again Fair Use?"

Post a Comment